Archives

All posts for the month November, 2017

Face-detecting systems in China now authorize payments, provide access to facilities, and track down criminals. Will other countries follow?

Availability: Now

by Will Knight

Shortly after walking through the door at Face++, a Chinese startup valued at roughly a billion dollars, I see my face, unshaven and looking a bit jet-lagged, flash up on a large screen near the entrance.

Having been added to a database, my face now provides automatic access to the building. It can also be used to monitor my movements through each room inside. As I tour the offices of Face++ (pronounced “face plus plus”), located in a suburb of Beijing, I see it appear on several more screens, automatically captured from countless angles by the company’s software. On one screen a video shows the software tracking 83 different points on my face simultaneously. It’s a little creepy, but undeniably impressive

Over the past few years, computers have become incredibly good at recognizing faces, and the technology is expanding quickly in China in the interest of both surveillance and convenience. Face recognition might transform everything from policing to the way people interact every day with banks, stores, and transportation services.

Technology from Face++ is already being used in several popular apps. It is possible to transfer money through Alipay, a mobile payment app used by more than 120 million people in China, using only your face as credentials. Meanwhile, Didi, China’s dominant ride-hailing company, uses the Face++ software to let passengers confirm that the person behind the wheel is a legitimate driver. (A “liveness” test, designed to prevent anyone from duping the system with a photo, requires people being scanned to move their head or speak while the app scans them.)

The technology figures to take off in China first because of the country’s attitudes toward surveillance and privacy. Unlike, say, the United States, China has a large centralized database of ID card photos. During my time at Face++, I saw how local governments are using its software to identify suspected criminals in video from surveillance cameras, which are omnipresent in the country. This is especially impressive—albeit somewhat dystopian—because the footage analyzed is far from perfect, and because mug shots or other images on file may be several years old.

Paying With Your Face

- Breakthrough Face recognition technology that is finally accurate enough to be widely used in financial transactions and other everyday applications.

- Why It Matters The technology offers a secure and extremely convenient method of payment but could raise privacy concerns.

- Key Players

– Face++

– Baidu

– Alibaba

- Availability

Now

Facial recognition has existed for decades, but only now is it accurate enough to be used in secure financial transactions. The new versions use deep learning, an artificial-intelligence technique that is especially effective for image recognition because it makes a computer zero in on the facial features that will most reliably identify a person (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2013: Deep Learning”).

“The face recognition market is huge,” says Shiliang Zhang, an assistant professor at Peking University who specializes in machine learning and image processing. Zhang heads a lab not far from the offices of Face++. When I arrived, his students were working away furiously in a dozen or so cubicles. “In China security is very important, and we also have lots of people,” he says. “Lots of companies are working on it.”

Employees simply show their face to gain entry to the company’s headquarters.

One such company is Baidu, which operates China’s most popular search engine, along with other services. Baidu researchers have published papers showing that their software rivals most humans in its ability to recognize a face. In January, the company proved this by taking part in a TV show featuring people who are remarkably good at identifying adults from their baby photos. Baidu’s system outshined them.

Now Baidu is developing a system that lets people pick up rail tickets by showing their face. The company is already working with the government of Wuzhen, a historic tourist destination, to provide access to many of its attractions without a ticket. This involves scanning tens of thousands of faces in a database to find a match, which Baidu says it can do with 99 percent accuracy.

Jie Tang, an associate professor at Tsinghua University who advised the founders of Face++ as students, says the convenience of the technology is what appeals most to people in China. Some apartment complexes use facial recognition to provide access, and shops and restaurants are looking to the technology to make the customer experience smoother. Not only can he pay for things this way, he says, but the staff in some coffee shops are now alerted by a facial recognition system when he walks in: “They say, ‘Hello, Mr. Tang.’”

Couldn’t make it to Cambridge? We’ve brought EmTech MIT to you!

Watch session videos

Article link: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/603494/10-breakthrough-technologies-2017-paying-with-your-face/

In China, you can use your face to get into your office, get on a train, or get a loan.

by Yiting Sun August 11, 2017

In China, face recognition is transforming many aspects of daily life. Employees at e-commerce giant Alibaba in Shenzhen can show their faces to enter their office building instead of swiping ID cards. A train station in western Beijing matches passengers’ tickets to their government-issued IDs by scanning their faces. If their face matches their ID card photo, the system deems their tickets valid and the station gate will open. The subway system in Hangzhou, a city about 125 miles southwest of Shanghai, employs surveillance cameras capable of recognizing faces to spot suspected criminals.

In China, face recognition is transforming many aspects of daily life. Employees at e-commerce giant Alibaba in Shenzhen can show their faces to enter their office building instead of swiping ID cards. A train station in western Beijing matches passengers’ tickets to their government-issued IDs by scanning their faces. If their face matches their ID card photo, the system deems their tickets valid and the station gate will open. The subway system in Hangzhou, a city about 125 miles southwest of Shanghai, employs surveillance cameras capable of recognizing faces to spot suspected criminals.

The technology powering many of these applications? Face++, the world’s largest face-recognition technology platform, currently used by more than 300,000 developers in 150 countries to identify faces, as well as images, text, and various kinds of government-issued IDs (see “50 Smartest Companies 2017: Face++”).

Other Chinese companies, such as Baidu and the startup SenseTime, also provide face-recognition technology to developers, but Face++’s popularity has been a boon for Megvii, the Beijing-based company that created and runs the platform. Founded in 2011 by three Tsinghua University graduates, Megvii is now valued at roughly a billion dollars and boasts approximately 530 employees, up from about 30 employees in 2014.

Megvii believes that as the Internet takes over more and more commercial and social functions, face recognition will become part of the Web’s infrastructure as a means of identification, though only for activities that require real identities. Other tech companies seem to be betting on this scenario, too; Samsung’s Galaxy S8 and S8+ phones support face recognition (for unlocking the devices), and Apple is rumored to be equipping its upcoming iPhone 8 with the technology.

Face ID, Megvii’s online identity authentication platform, is one way Face++ is being integrated into the Internet’s infrastructure. (Face ID’s face-comparison API interface utilizes Face++ technology.) Nearly 90 percent of China’s roughly 200 top Internet companies use Face ID, according to Yin. It’s particularly popular with online financial services since they need to authenticate user identities remotely. (To avoid people tricking them with a photograph, these apps usually perform a “liveness test” that requires users to speak or move their heads.)

Xiaohua, which operates a virtual bank that grants loans and offers payments by installments through a mobile app called Xiaohua Qianbao (“Little Flower Wallet”), is a typical Face ID customer. Users scan their face using the app to get approved for loans and to ensure that nobody can authorize actions in the app if their phone is lost or stolen. “Xiaohua Qianbao is a purely online borrowing and lending product, so our first need is fraud prevention,” says Lingpeng Huang, a cofounder of Xiaohua. “Face recognition has eliminated the risk of fake identities.”

Megvii trains the algorithms that power Face++ and Face ID by feeding large data sets into a deep-learning engine called Brain++. (Deep learning involves feeding examples into a large, many-layered neural network, and tweaking its parameters until it accurately recognizes the desired features, such as a particular person’s face.)

To amass huge amounts of training data, Megvii let most developers use Face++ for free during the platform’s first two years of availability in 2012 and 2013. Megvii also purchases photos from data-collection companies to aid its training.

Recommended for You

The company built Brain++ in 2015 and says having a self-developed deep-learning engine helps it train its algorithms more efficiently. “[It] translates into more competitiveness for our products,” says Jian Sun, Megvii’s chief scientist.

Another advantage of having its own deep-learning platform: Megvii can customize its face-recognition technology for different customers easily. That matters because a police department, for example, will value accuracy above everything else, but a company looking to use face recognition in a mobile app needs to ensure that the software is small enough to fit inside the app—without sacrificing too much accuracy.

When CEO Qi Yin launched Megvii, he wanted to gain traction in a few key areas. “An AI company has to be No. 1 in one or two core industries first [to succeed],” he says.

Now that Face++ is entrenched in banking and finance, Megvii’s cofounders have plans to integrate its face recognition and other computer-vision technologies into more industries, such as retail and self-driving cars. For that to happen, the company needs to show those industries how they will benefit, such as how much fraud its technology can reduce every year, says Jiansheng Chen, an associate professor at Tsinghua University who studies computer vision.

Couldn’t make it to Cambridge? We’ve brought EmTech MIT to you!

Watch session videos

Article link: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/608598/when-a-face-is-worth-a-billion-dollars

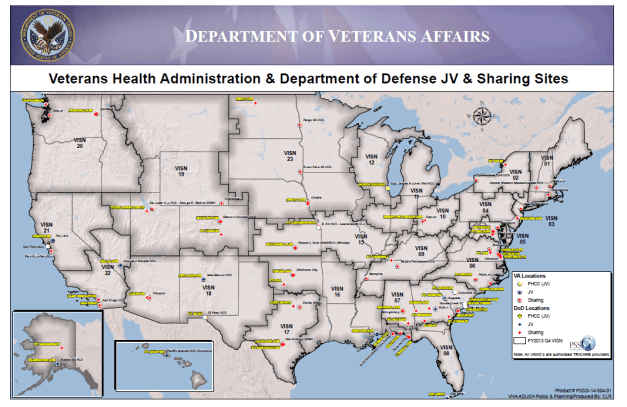

VA-DoD JSP FY2016-2018 Combined Draft VA DoD consolidation – Final (508 Compliance Reformatted with Signature)

Authored by the Joint Executive Committee: https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Access-to-Healthcare/DoD-VA-Sharing-Initiatives/Joint-Oversight/JEC

Physicians have long been quick to point out the social contract they have with their patients and the community in which they live. Sadly, several baser trends have gathered steam that have the potential to diminish the nobler aspects of the medical profession.

patients and the community in which they live. Sadly, several baser trends have gathered steam that have the potential to diminish the nobler aspects of the medical profession.

For example, the ever-increasing commercialization of health care has resulted in the perception that medicine is now primarily a business rather than a vocation. Reports of annual salaries of a million dollars or more are common and, currently, the average salary for primary care doctors is about $200,000 and the average for specialists is about $300,000.1

Unfortunately, some doctors have either been enticed or forced to practice for the sake of the financial bottom line rather than for the greatest benefit to their patients. This has led to many doctors leaving private practice to work for institutions. In fact, more American doctors now work for institutions than are in private practice. These doctors are often faced with the same commercial interests as doctors in private practice when they report to administrators who care most, if not only, about the financial bottom line.

For example, many health care administrators admonish doctors for not ordering unnecessary, expensive tests or for spending too much time with each patient. The latter is especially exasperating for doctors who care for elderly, intellectually disabled, or mentally ill patients whose problems take much time to resolve. In addition, doctors who care for intellectually disabled patients have more trouble finding an ER or hospital to care for these patients as they do for “normal” patients. That can lead to these patients suffering unnecessary (and expensive) morbidity or mortality.

Today, doctors are spending too many hours a day completing electronic health records, which don’t help all that much with personalized patient care even if they are useful for billing.

Too many doctors work for the marketing section of pharmaceutical and medical device companies. That is, they serve on the companies’ speakers bureaus where they present at medical centers, meetings, or conferences, using power point slides provided by the company that accentuate the positive aspects and gloss over the negative aspects of an expensive drug or device. These doctors are paid well for these presentations, often scheduled by the companies.

Other doctors prescribe expensive drugs because patients come to them with coupons for a free first prescription that they found in a direct-to-consumer advertisement by a pharmaceutical company. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the only other developed country that allows such advertising is New Zealand. Rather than spend precious time with the patient discussing why the expensive drug is unnecessary, some doctors simply comply with the patient’s request. Unfortunately, once the first prescription is written, those that follow usually are for the same expensive drug. Just like the old adage about lunches, there’s no such thing as a free drug.

Increasing numbers of doctors prescribe expensive drugs when less expensive generic drugs would work just as well or prescribe unnecessary drugs, such as opioids, having been enticed to do so by very persuasive drug representatives who bear gifts such as food and tickets to games or the theater. Any doctor who accepts a gift from a pharmaceutical or device company representative, when the motive is clearly to get the doctor to prescribe their drug or device, is working for the company and not the patient.

The 2010 Physician Payment Sunshine Act was designed to increase transparency about financial relationships between doctors and teaching hospitals and manufacturers of drugs, medical devices, and biologics. The Act requires all pharmaceutical and medical device companies to keep a record of all money given to doctors and teaching hospitals. In 2015, $8.09 billion was given to 1,118 teaching hospitals and to 632,000 doctors. Slightly more than half of the money given to doctors in 2015 was provided for research, but the rest was for honoraria and gifts. Some, but certainly not all, of the honoraria were legitimate reimbursements to doctors who provided sound medical and scientific advice to the companies. The amount of money given for honoraria in 2015 decreased by 50% and for gifts by 30% compared with 2014. Similar data for 2016 are essentially unchanged from 2015.

Pharmaceutical and medical device companies pay for clinical trials to test their new drugs or devices, a requirement before the FDA will approve their products. These clinical trials and other drug research are conducted by doctors and other scientists and are published in medical journals. This is a means of alerting doctors of new research, but it is also a means of advertising the drug or device. The problem is that too often many of these published studies are then retracted (withdrawn or disavowed) by the journal because of problems with the research.2 While some retractions are unavoidable, the exorbitant number of retractions reported makes one wonder about how carefully the studies are being scrutinized.

Publishing practice guidelines are meant to assist doctors in making decisions about treatments. However, many, or in some cases most, of the doctors who serve on the guideline committees are paid in some way by the pharmaceutical or device companies that manufacture the products in the guideline. This begs the question: How unbiased can these doctors be?

So, what must be done? The simple answer is for all doctors to remember why they chose medicine as a profession. As a medical educator for more than 40 years, I know that medical students’ stated reasons for entering medicine have not changed one bit. They, like the majority of doctors, want to have a noble profession of taking care of patients. It would be well for all doctors to read (again?) the excellent 1927 publication, The Care of the Patient, by Frances Peabody. He stated that, “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is caring for the patient.”3

If physicians are truly allowed to care for patients, they must refuse to take less time with patients than needed, to order unnecessary tests, to prescribe unnecessary drugs or expensive drugs when generic or other less expensive drugs would work as well, to accept gifts from pharmaceutical and device representatives, to publish articles that contain tainted data, and to complete forms that do little or nothing for patient care. Those doctors who already practice in this way need to encourage all of their colleagues to do the same. Those who deem this to be an impossible task should remember Nelson Mandala’s sage advice, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.”

Article link: https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/medicine-profession-distress/#.WgsnW5b42yx.twitter

References

- Peckham C. Medscape physician compensation report 2015. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/compensation-2015-overview-6006679. Published April 21, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2017.

- Castillo M. The fraud and retraction epidemic. Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1653-1654.

- Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88:877-882.

Large hospital systems throughout the country are struggling with today’s healthcare economics. (Photo by Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

Large hospital systems throughout the country are struggling with today’s healthcare economics. (Photo by Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

A strange thing happened last year in some the nation’s most established hospitals and health systems. Hundreds of millions of dollars in income suddenly disappeared.

This article, part two of a series that began with a look at primary care disruption, examines the economic struggles of inpatient facilities, the even harsher realities in front of them, and why hospitals are likely to aggravate, not address, healthcare’s rising cost issues.

According to the Harvard Business Review, several big-name hospitals reported significant declines and, in some cases, net losses to their FY 2016 operating margins. Among them, Partners HealthCare, New England’s largest hospital network, lost $108 million; the Cleveland Clinic witnessed a 71% decline in operating income; and MD Anderson, the nation’s largest cancer center, dropped $266 million.

How did some of the biggest brands in care delivery lose this much money? The problem isn’t declining revenue. Since 2009, hospitals have accounted for half of the $240 billion spending increase among private U.S. insurers. It’s not that increased competition is driving price wars, either. On the contrary, 1,412 hospitals have merged since 1998, primarily to increase their clout with insurers and raise prices. Nor is it a consequence of people needing less medical care. The prevalence chronic illness continues to escalate, accounting for 75% of U.S. healthcare costs, according to the CDC

Part Of The Problem Is Rooted In The Past

From the late 19th century to the early 20th, hospitals were places the sick went to die. For practically everyone else, healthcare was delivered by house call. With the introduction of general anesthesia and the discovery of powerful antibiotics, medical care began moving from people’s homes to inpatient facilities. And by the 1950s, some 6,000 hospitals had sprouted throughout the country. For all that expansion, hospital costs remained relatively low. By the time Medicare rolled out in 1965, healthcare consumed just 5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Today, that number is 18%.

Hospitals have contributed to the cost hike in recent decades by: (1) purchasing redundant, expensive medical equipment and generating excess demand, (2) hiring highly paid specialists to perform ever-more complex procedures with diminishing value, rather than right-sizing their work forces, and (3) tolerating massive inefficiencies in care delivery (see “the weekend effect”).

How Hospital CEOs See It

Most hospital leaders acknowledge the need to course correct, but very few have been able to deliver care that’s significantly more efficient or cost-effective than before. Instead, hospitals in most communities have focused on reducing and eliminating competition. As a result, a recent study found that 90% of large U.S. cities were “highly concentrated for hospitals,” allowing those that remain to increase their market power and prices.

Historically, such consolidation (and price escalation) has enabled hospitals to offset higher expenses. As of late, however, this strategy is proving difficult. Here’s how some leaders explain their recent financial struggles:

“Our expenses continue to rise, while constraints by government and payers are keeping our revenues flat.”

Brigham Health president Dr. Betsy Nabel offered this explanation in a letter to employees this May, adding that the hospital will “need to work differently in order to sustain our mission for the future.”

A founding member of Partners HealthCare in Boston, Brigham & Women’s Hospital (BWH) is the second-largest research hospital in the nation, with over $640 million in funding. Its storied history dates back more than a century. But after a difficult FY 2016, BWH offered retirement buyouts to 1,600 employees, nearly 10% of its workforce.

Three factors contributed to the need for layoffs: (1) reduced reimbursements from payers, including the Massachusetts government, which limits annual growth in healthcare spending to 3.6%, a number that will drop to 3.1% next year, (2) high capital costs, both for new buildings and for the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system, and (3) high labor expenses among its largely unionized workforce.

“The patients are older, they’re sicker … and it’s more expensive to look after them.”

That, along with higher labor and drug costs, explained the Cleveland Clinic’s economic headwinds, according to outgoing CEO Dr. Toby Cosgrove. And though he did not specifically reference Medicare, years of flat reimbursement levels have resulted in the program paying only 90% of hospital costs for the “older,” “sicker” and “more expensive” patients.

Of note, these operating losses occurred despite the Clinic’s increase in year-over-year revenue. Operating income is on the upswing in 2017, but it remains to be seen whether the health system’s new CEO can continue to make the same assurances to employees as his predecessor that, “We have no plans for workforce reduction.”

“Salaries and wages and … and increased consulting expenses primarily related to the Epic EHR project.”

Leaders at MD Anderson, the largest of three comprehensive cancer centers in the United States, blamed these three factors for the institution’s operational losses. In a statement, executives attributed a 77% drop in adjusted income last August to “a decrease in patient revenues as a result of the implementation of the new Epic Electronic Health Record system.”

Following a reduction of nearly 1,000 jobs (5% of its workforce) in January 2017, and the resignation of MD Anderson’s president this March, a glimmer of hope emerged. The institution’s operating margins were in the black in the first quarter of 2017, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Making Sense Of Hospital Struggles

The challenges confronting these hospital giants mirror the difficulties nearly all community hospitals face. Relatively flat Medicare payments are constraining revenues. The payer mix is shifting to lower-priced patients, including those on Medicaid. Many once-profitable services are moving to outpatient venues, including physician-owned “surgicenters” and diagnostic facilities. And as one of the most unionized industries, hospitals continue to increase wages while drug companies continue raising prices – at three times the rate of healthcare inflation.

Though these factors should inspire hospital leaders to exercise caution when investing, many are spending millions in capital to expand their buildings and infrastructure with hopes of attracting more business from competitors. And despite a $44,000 federal nudge to install EHRs, hospitals are finding it difficult to justify the investment. Digital records are proven to improve patient outcomes, but they also slow down doctors and nurses. According to the annual Deloitte “Survey of US Physicians,” 7 out of 10 physicians report that EHRs reduce productivity, thereby raising costs.

Harsh Realities Ahead For Hospitals

Although nearly every hospital talks about becoming leaner and more efficient, few are fulfilling that vision. Given the opportunity to start over, our nation would build fewer hospitals, eliminate the redundancy of high-priced machines, and consolidate operating volume to achieve superior quality and lower costs.

Instead, hospitals are pursuing strategies of market concentration. As part of that approach, they’re purchasing physician practices at record rates, hoping to ensure continued referral volume, regardless of the cost.

Today, commercial payers bear the financial brunt of hospital inefficiencies and high costs but, at some point, large purchasers will say “no more.” These insurers may soon get help from the nation’s largest purchaser, the federal government. Last month, President Donald Trump issued an executive order with language suggesting the administration and federal agencies may seek to limit provider consolidation, lower barriers to entry and prevent “abuses of market power.”

With pressure mounting, hospital administrators find themselves wedged deeper between a rock and a hard place. They know doctors, nurses, and staff will fight the changes required to boost efficiency, especially those that involve increasing productivity or lowering headcount. But at their same time, their bargaining power is diminishing as health-plan consolidation continues. The four largest insurance companies now own 83% of the national market.

What’s more, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced last week a $1.6 billion cut to certain Medicare Part B drug payments along with reduced reimbursements for off-campus hospital outpatient departments in 2018. CMS said these moves will “provide a more level playing field for competition between hospitals and physician practices by promoting greater payment alignment.”

The American healthcare system is stuck with investments that made sense decades ago but that now result in hundreds of billions of dollars wasted each year. Hospitals are a prime example. That’s why we shouldn’t count on hospital administrators to solve America’s cost challenges.

Change will need to come from outside the traditional healthcare system. The final part of this series will explore three potential solutions and highlight the innovative companies leading the effort.

Article link: read:https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertpearl/2017/11/07/hospitals-losing-millions/

Magazine: Spring 2017 Issue Research Feature

There are few management skills more powerful than the discipline of clearly articulating the problem you seek to solve before jumping into action.

It’s hard to pick up a current business publication without reading about the imperative to change. The world, this line of argument suggests, is evolving at an ever-faster rate, and organizations that do not adapt will be left behind. Left silent in these arguments is which organizations will drive that change and how they will do it. Academic research suggests that the ability to incorporate new ideas and technologies into existing ways of doing things plays a big role in separating leaders from the rest of the pack,1 and studies clearly show that it is easier to manage a sequence of bite-sized changes than one huge reorganization or change initiative.2 But, while many organizations strive for continuous change and learning, few actually achieve those goals on a regular basis.3 Two of the authors have studied and tried to make change for more than two decades, but it was a frustrating meeting that opened our eyes to one of the keys to leading the pack rather than constantly trying to catch up.

In the late 1990s, one of the authors, Don Kieffer, was ready to launch a big change initiative: implementing the Toyota production system in one of Harley-Davidson Inc.’s engine plants. He hired a seasoned consultant, Hajime Oba, to help. On the appointed day, Mr. Oba arrived, took a tour of the plant, and then returned to Don’s office, where Don started asking questions: When do we start? What kind of results should I expect? How much is it going to cost me? But, Mr. Oba wouldn’t answer those questions. Instead he responded repeatedly with one of his own: “Mr. Kieffer, what problem are you trying to solve?” Don was perplexed. He was ready to spend money and he had one of the world’s experts on the Toyota production system in his office, but the expert (Mr. Oba) wouldn’t tell Don how to get started.

The day did not end well. Don grew exasperated with what seemed like a word game, and Mr. Oba, tired of not getting an answer to his question, eventually walked out of Don’s office. But, despite the frustration on both sides, we later realized that Mr. Oba was trying to teach Don one of the foundational skills in leading effective change: formulating a clear problem statement. Since Mr. Oba’s visit, two of the authors have studied and worked with dozens of organizations and taught over 1,000 executives. We have helped organizations with everything from managing beds in a cardiac surgery unit to sequencing the human genome.4 Based on this experience, we have come to believe that problem formulation is the single most underrated skill in all of management practice.

There are few questions in business more powerful than “What problem are you trying to solve?” In our experience, leaders who can formulate clear problem statements get more done with less effort and move more rapidly than their less-focused counterparts. Clear problem statements can unlock the energy and innovation that lies within those who do the core work of your organization.

As valuable as good problem formulation can be, it is rarely practiced. Psychologists and cognitive scientists have suggested that the brain is prone to leaping straight from a situation to a solution without pausing to define the problem clearly. Such “jumping to conclusions” can be effective, particularly when done by experts facing extreme time pressure, like fighting a fire or performing emergency surgery. But, when making change, neglecting to formulate a clear problem statement often prevents innovation and leads to wasted time and money. In this article, we hope to both improve your problem formulation skills and introduce a simple method for solving those problems.

How Our Minds Solve Problems

Research done over the last few decades indicates that the human brain has at least two different methods for tackling problems, and which method dominates depends on both the individual’s current situation and the surrounding context. A large and growing collection of research indicates that it is useful to distinguish between two modes of thinking, which psychologists and cognitive scientists sometimes call automatic processing and conscious processing (also sometimes known as system 1 and system 2).5 These two modes tackle problems differently and do so at different speeds.

Conscious Processing

Conscious processing represents the part of your brain that you control. When you are aware that you are thinking about something, you are using conscious processing. Conscious cognition can be both powerful and precise. It is the only process in the brain capable of forming a mental picture of a situation at hand and then playing out different possible scenarios, even if those scenarios have never happened before.6 With this ability, humans can innovate and learn in ways not available to other species.

Despite its power, conscious processing is “expensive” in at least three senses. First, it is much slower than its automatic counterpart. Second, our capacity to do it is quite finite, so a decision to confront one problem means that you don’t have the capacity to tackle another one at the same time. Third, conscious processing burns scarce energy and declines when people are tired, hungry, or distracted. Because of these costs, the human brain system has evolved to “save” conscious processing for when it is really needed and, when possible, relies on the “cheaper” automatic processing mode.

Automatic Processing

Automatic processing works differently from its conscious counterpart. We don’t have control over it or even feel it happening. Instead, we are only aware of the results, such as a thought that simply pops into your head or a physical response like hitting the brake when the car in front of you stops suddenly. You cannot directly instruct your automatic processing functions to do something; instead, they constitute a kind of “back office” for your brain. When a piece of long-sought-after information just pops into your head, hours or days after it was needed, you are experiencing the workings of your automatic processing functions.

When we tackle a problem consciously, we proceed logically, trying to construct a consistent path from the problem to the solution. In contrast, the automatic system works based on what is known as association or pattern matching. When confronted with a problem, the automatic processor tries to match that current challenge to a previous situation and then uses that past experience as a guide for how to act. Every time we instinctively react to a stop sign or wait for people to exit an elevator before entering, we rely on automatic processing’s pattern matching to determine our choice of action.

Our “associative machine” can be amazingly adept at identifying subtle patterns in the environment. For example, the automatic processing functions are the only parts of the brain capable of processing information quickly enough to return a serve in tennis or hit a baseball. Psychologist Gary Klein has documented how experienced professionals who work under intense time pressure, like surgeons and firefighters, use their past experience to make split-second decisions.7 Successful people in these environments rely on deep experience to almost immediately link the current situation to the appropriate action.

However, because it relies on patterns identified from experience, automatic processing can bias us toward the status quo and away from innovative solutions. It should come as little surprise that breakthrough ideas and technologies sometimes come from relative newcomers who weren’t experienced enough to “know better.” Research suggests that innovations often result from combining previously disparate perspectives and experiences.8 Furthermore, the propensity to rely on previous experiences can lead to major industrial accidents like Three Mile Island if a novel situation is misread as an established pattern and therefore receives the wrong intervention.9

That said, unconscious processing can also play a critical and positive role in innovation. As we have all experienced, sometimes when confronting a hard problem, you need to step away from it for a while and think about something else. There is some evidence for the existence of such “incubation” effects. Unconscious mental processes may be better able to combine divergent ideas to create new innovations.10 But it also appears that such innovations can’t happen without the assistance of the conscious machinery. Prior to the “aha” moment, conscious effort is required to direct attention to the problem at hand and to immerse oneself in relevant data. After the flash of insight, conscious attention is again needed to evaluate the resulting combinations.

The Discipline of Problem Formulation

When the brain’s associative machine is confronted with a problem, it jumps to a solution based on experience. To complement that fast thinking with a more deliberate approach, structured problem-solving entails developing a logical argument that links the observed data to root causes and, eventually, to a solution. Developing this logical path increases the chance that you will leverage the strengths of conscious processing and may also create the conditions for generating and then evaluating an unconscious breakthrough. Creating an effective logical chain starts with a clear description of the problem and, in our experience, this is where most efforts fall short.

A good problem statement has five basic elements:

- It references something the organization cares about and connects that element to a clear and specific goal;

- it contains a clear articulation of the gap between the current state and the goal;

- the key variables — the target, the current state, and the gap — are quantifiable;

- it is as neutral as possible concerning possible diagnoses or solutions; and

- it is sufficiently small in scope that you can tackle it quickly.

Is your problem important? The first rule of structured problem-solving is to focus its considerable power on issues that really matter. You should be able to draw a direct path from the problem statement to your organization’s overall mission and targets. The late MIT Sloan School professor Jay Forrester, one of the fathers of modern digital computing, once wrote that “very often the most important problems are but little more difficult to handle than the unimportant.”11 If you fall into the trap of initially focusing your attention on peripheral issues for “practice,” chances are you will never get around to the work you really need to do.

Mind the gap. Decades of research suggest that people work harder and are more focused when they face clear, easy-to-understand goals.12 More recently, psychologists have shown that mentally comparing a desired state with the current one, a process known as mental contrasting, is more likely to lead people to change than focusing only on the future or on current challenges.13 Recent work also suggests that people draw considerable motivation from the feeling of progress, the sense that their efforts are moving them toward the goal in question.14 A good problem statement accordingly contains a clear articulation of the gap that you are trying to close.

Quantify even if you can’t measure. Being able to measure the gap between the current state and your target precisely will support an effective project. However, structured problem-solving can be successfully applied to settings that do not yield immediate and precise measurements, because many attributes can be subjectively quantified even if they cannot be objectively measured. Quantification of an attribute simply means that it has a clear direction — more of that attribute is better or worse — and that you can differentiate situations in which that attribute is low or high. For example, many organizations struggle with so-called “soft” variables like customer satisfaction and employee trust. Though these can be hard to measure, they can be quantified; in both cases, we know that more is better. Moreover, once you start digging into an issue, you often discover ways to measure things that weren’t obvious at the outset. For example, a recent project by a student in our executive MBA program tackled an unproductive weekly staff meeting. The student began his project by creating a simple web-based survey to capture the staff’s perceptions of the meeting, thus quickly generating quantitative data.

Remain as neutral as possible. A good problem formulation presupposes as little as practically possible concerning why the problem exists or what might be the appropriate solution. That said, few problem statements are perfectly neutral. If you say that your “sales revenue is 22% behind its target,” that formulation presupposes that problem is important to your organization. The trick is to formulate statements that are actionable and for which you can draw a clear path to the organization’s overarching goals.

Is your scope down? Finally, a good problem statement is “scoped down” to a specific manifestation of the larger issue that you care about. Our brains like to match new patterns, but we can only do so effectively when there is a short time delay between taking an action and experiencing the outcome.15 Well-structured problem-solving capitalizes on the natural desire for rapid feedback by breaking big problems into little ones that can be tackled quickly. You will learn more and make faster progress if you do 12 one-month projects instead of one 12-month project.

To appropriately scope projects, we often use the “scope-down tree,” a tool we learned from our colleague John Carrier, who is a senior lecturer of system dynamics at MIT. The scope-down tree allows the user to plot a clear path between a big problem and a specific manifestation that can be tackled quickly. (See “Narrowing a Problem’s Scope.”)

Managers we work with often generate great results when they have the discipline to scope down their projects to an area where they can, say, make a 30% improvement in 60 days. The short time horizon focuses them on a set of concrete interventions that they can execute quickly. This kind of “small wins” strategy has been discussed by a variety of organizational scholars, but it remains rarely practiced.16

Four Common Mistakes

Having taught this material extensively, we have observed four common failure modes. Avoiding these mistakes is critical to formulating effective problem statements and focusing your attention on the issues that really matter to you and your organization.

1. Failing to Formulate the Problem

The most common mistake is skipping problem formulation altogether. People often assume that they all already agree on the problem and should just get busy solving it. Unfortunately, such clarity and commonality rarely exist.

2. Problem Statement as Diagnosis or Solution

Another frequent mistake is formulating a problem statement that presupposes either the diagnosis or the solution. A problem statement that presumes the diagnosis will often sound like “The problem is we lack the right IT capabilities,” and one that presumes a solution will sound like “The problem is that we haven’t spent the money to upgrade our IT system.” Neither is an effective problem statement because neither references goals or targets that the organization really cares about. The overall target is implicit, and the person formulating the statement has jumped straight to either a diagnosis or a solution. Allowing diagnoses or proposed solutions to creep into problem statements means that you have skipped one or more steps in the logical chain and therefore missed an opportunity to engage in conscious cognitive processing. In our experience, this mistake tends to reinforce existing disputes and often worsens functional turf wars.

3. Lack of a Clear Gap

A third common mistake is failing to articulate a clear gap. These problem statements sound like “We need to improve our brand” or “Sales have to go up.” The lack of a clear gap means that people are not engaging in clear mental contrasting and creates two related problems. First, people don’t know when they have achieved the goal, making it difficult for them to feel good about their efforts. Second, when people address poorly formulated problems, they tend to do so with large, one-size-fits-all solutions that rarely produce the desired results.

4. The Problem Is Too Big

Many problem statements are too big. Broadly scoped problem formulations lead to large, costly, and slow initiatives; problem statements focused on an acute and specific manifestation lead to quick results, increasing both learning and confidence. Use John Carrier’s scope-down tree and find a specific manifestation of your problem that creates the biggest headaches. If you can solve that instance of the problem, you will be well on your way to changing your organization for the better.

Formulating good problem statements is a skill anybody can learn, but it takes practice. If you leverage input from your colleagues to build your skills, you will get to better formulations more quickly. While it is often difficult to formulate a clear statement of the challenges you face, it is much easier to critique other people’s efforts, because you don’t have the same experiences and are less invested in a particular outcome. When we ask our students to coach each other, their problem formulations often improve dramatically in as little as 30 minutes.

Structured Problem-Solving

As you tackle more complex problems, you will need to complement good problem formulation with a structured approach to problem-solving. Structured problem-solving is nothing more than the essential elements of the scientific method — an iterative cycle of formulating hypotheses and testing them through controlled experimentation repackaged for the complexity of the world outside the laboratory. W. Edwards Deming and his mentor Walter Shewhart, the grandfathers of total quality management, were perhaps the first to realize that this discipline could be applied on the factory floor. Deming’s PDCA cycle, or Plan-Do-Check-Act, was a charge to articulate a clear hypothesis (a Plan), run an experiment (Do the Plan), evaluate the results (Check), and then identify how the results inform future plans (Act). Since Deming’s work, several variants of structured problem-solving have been proposed, all highlighting the basic value of iterating between articulating a hypothesis, testing it, and then developing the next hypothesis. In our experience, making sure that you use a structured problem-solving method is far more important than which particular flavor you choose.

In the last two decades, we have done projects using all of the popular methods and supervised and coached over 1,000 student projects using them. Our work has led to a hybrid approach to guiding and reporting on structured problem-solving that is both simple and effective. We capture our approach in a version of Toyota’s famous A3 form that we have modified to enable its use for work in settings other than manufacturing.17 (See “Tracking Projects Using an A3 Form.”)

The world’s second-most-valuable cryptocurrency is also its most interesting—but in order to understand it, you must first understand its origins.

by Mike Orcutt October 26, 2017

In the beginning, there was Bitcoin. The cryptocurrency has for many become synonymous with the idea of digital money, rising to a market capitalization of nearly $100 billion. But the second-most-valuable currency, Ether, may be far more interesting than its headline-grabbing older sibling. To understand why it’s so popular, it helps to understand why the software that runs it, called Ethereum, exists in the first place..

This piece first appeared in our new twice-weekly newsletter, Chain Letter, which covers the world of blockchain and cryptocurrencies. Sign up here – it’s free!

On Halloween in 2008, someone or some group of people using the name Satoshi Nakamoto published a white paper describing a system that would rely on a “decentralized” network of computers to facilitate the peer-to-peer exchange of value (bitcoins). Those computers would verify and record every transaction in a shared, encrypted accounting ledger. Nakamoto called this ledger a “blockchain,” because it’s composed of groups of transactions called “blocks,” each one cryptographically linked to the one preceding it.

Learn more about blockchain and its role in the crypto-economy.

Bitcoin eventually took off, and soon people latched onto the idea that its blockchain could be used to do other things, from tracking medical data to executing complex financial transactions (see “Why Bitcoin Could Be Much More Than a Currency”). But its design, intended specifically for a currency, limited the range of applications it could support, and Bitcoin aficionados started brainstorming new approaches.

It was from this primordial soup that Ethereum emerged.

Recommended for You

In a 2013 white paper, Vitalik Buterin, then just 19, laid out his plan for a blockchain system that could also facilitate all sorts of “decentralized applications.” Buterin achieved this in large part by baking a programming language into Ethereum so that people could customize it to their purposes. These new apps are based on so-called smart contracts—computer programs that execute transactions, usually involving the transfer of currency, according to stipulations agreed upon by the participants.

Imagine, for example, that you want to send your friend some cryptocurrency automatically, at a specific time. There’s a smart contract for that. More complex smart contracts even allow for the creation of entirely new cryptocurrencies. That feature is at the heart of most initial coin offerings. (What the Hell Is an ICO? ← here’s a primer)

The processing power needed to run the smart contracts comes from the computers in an open, distributed network. Those computers also verify and record transactions in the blockchain. Ether tokens, which are currently worth about $300 apiece, are the reward for these contributions. Whereas Bitcoin is the first shared global accounting ledger, Ethereum is supposed to be the first shared global computer. The technology is nascent, and there are plenty of kinks to iron out, but that’s what all the fuss is about.

Article link: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609227/this-is-the-reason-ethereum-exists