What the firm found challenges some basic assumptions about how this technology really works.

March 27, 2025

The AI firm Anthropic has developed a way to peer inside a large language model and watch what it does as it comes up with a response, revealing key new insights into how the technology works. The takeaway: LLMs are even stranger than we thought.

The Anthropic team was surprised by some of the counterintuitive workarounds that large language models appear to use to complete sentences, solve simple math problems, suppress hallucinations, and more, says Joshua Batson, a research scientist at the company.

It’s no secret that large language models work in mysterious ways. Few—if any—mass-market technologies have ever been so little understood. That makes figuring out what makes them tick one of the biggest open challenges in science.

But it’s not just about curiosity. Shedding some light on how these models work exposes their weaknesses, revealing why they make stuff up and why they can be tricked into going off the rails. It helps resolve deep disputes about exactly what these models can and can’t do. And it shows how trustworthy (or not) they really are.

Batson and his colleagues describe their new work in two reports published today. The first presents Anthropic’s use of a technique called circuit tracing, which lets researchers track the decision-making processes inside a large language model step by step. Anthropic used circuit tracing to watch its LLM Claude 3.5 Haiku carry out various tasks. The second (titled “On the Biology of a Large Language Model”) details what the team discovered when it looked at 10 tasks in particular.

“I think this is really cool work,” says Jack Merullo, who studies large language models at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and was not involved in the research. “It’s a really nice step forward in terms of methods.”

Circuit tracing is not itself new. Last year Merullo and his colleagues analyzed a specific circuit in a version of OpenAI’s GPT-2, an older large language model that OpenAI released in 2019. But Anthropic has now analyzed a number of different circuits inside a far larger and far more complex model as it carries out multiple tasks. “Anthropic is very capable at applying scale to a problem,” says Merullo.

Eden Biran, who studies large language models at Tel Aviv University, agrees. “Finding circuits in a large state-of-the-art model such as Claude is a nontrivial engineering feat,” he says. “And it shows that circuits scale up and might be a good way forward for interpreting language models.”

Circuits chain together different parts—or components—of a model. Last year, Anthropic identified certain components inside Claudethat correspond to real-world concepts. Some were specific, such as “Michael Jordan” or “greenness”; others were more vague, such as “conflict between individuals.” One component appeared to represent the Golden Gate Bridge. Anthropic researchers found that if they turned up the dial on this component, Claude could be made to self-identify not as a large language model but as the physical bridge itself.

The latest work builds on that research and the work of others, including Google DeepMind, to reveal some of the connections between individual components. Chains of components are the pathways between the words put into Claude and the words that come out.

“It’s tip-of-the-iceberg stuff. Maybe we’re looking at a few percent of what’s going on,” says Batson. “But that’s already enough to see incredible structure.”

Growing LLMs

Researchers at Anthropic and elsewhere are studying large language models as if they were natural phenomena rather than human-built software. That’s because the models are trained, not programmed.

“They almost grow organically,” says Batson. “They start out totally random. Then you train them on all this data and they go from producing gibberish to being able to speak different languages and write software and fold proteins. There are insane things that these models learn to do, but we don’t know how that happened because we didn’t go in there and set the knobs.”

Sure, it’s all math. But it’s not math that we can follow. “Open up a large language model and all you will see is billions of numbers—the parameters,” says Batson. “It’s not illuminating.”

Anthropic says it was inspired by brain-scan techniques used in neuroscience to build what the firm describes as a kind of microscope that can be pointed at different parts of a model while it runs. The technique highlights components that are active at different times. Researchers can then zoom in on different components and record when they are and are not active.

Take the component that corresponds to the Golden Gate Bridge. It turns on when Claude is shown text that names or describes the bridge or even text related to the bridge, such as “San Francisco” or “Alcatraz.” It’s off otherwise.

Yet another component might correspond to the idea of “smallness”: “We look through tens of millions of texts and see it’s on for the word ‘small,’ it’s on for the word ‘tiny,’ it’s on for the French word ‘petit,’ it’s on for words related to smallness, things that are itty-bitty, like thimbles—you know, just small stuff,” says Batson.

Having identified individual components, Anthropic then follows the trail inside the model as different components get chained together. The researchers start at the end, with the component or components that led to the final response Claude gives to a query. Batson and his team then trace that chain backwards.

Odd behavior

So: What did they find? Anthropic looked at 10 different behaviors in Claude. One involved the use of different languages. Does Claude have a part that speaks French and another part that speaks Chinese, and so on?

The team found that Claude used components independent of any language to answer a question or solve a problem and then picked a specific language when it replied. Ask it “What is the opposite of small?” in English, French, and Chinese and Claude will first use the language-neutral components related to “smallness” and “opposites” to come up with an answer. Only then will it pick a specific language in which to reply. This suggests that large language models can learn things in one language and apply them in other languages.

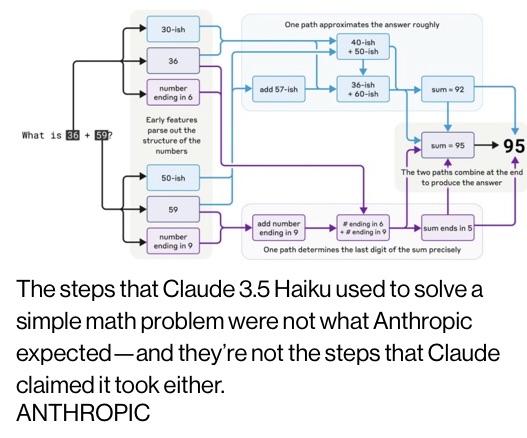

Anthropic also looked at how Claude solved simple math problems. The team found that the model seems to have developed its own internal strategies that are unlike those it will have seen in its training data. Ask Claude to add 36 and 59 and the model will go through a series of odd steps, including first adding a selection of approximate values (add 40ish and 60ish, add 57ish and 36ish). Towards the end of its process, it comes up with the value 92ish. Meanwhile, another sequence of steps focuses on the last digits, 6 and 9, and determines that the answer must end in a 5. Putting that together with 92ish gives the correct answer of 95.

And yet if you then ask Claude how it worked that out, it will say something like: “I added the ones (6+9=15), carried the 1, then added the 10s (3+5+1=9), resulting in 95.” In other words, it gives you a common approach found everywhere online rather than what it actually did. Yep! LLMs are weird. (And not to be trusted.)

This is clear evidence that large language models will give reasons for what they do that do not necessarily reflect what they actually did. But this is true for people too, says Batson: “You ask somebody, ‘Why did you do that?’ And they’re like, ‘Um, I guess it’s because I was— .’ You know, maybe not. Maybe they were just hungry and that’s why they did it.”

Biran thinks this finding is especially interesting. Many researchers study the behavior of large language models by asking them to explain their actions. But that might be a risky approach, he says: “As models continue getting stronger, they must be equipped with better guardrails. I believe—and this work also shows—that relying only on model outputs is not enough.”

A third task that Anthropic studied was writing poems. The researchers wanted to know if the model really did just wing it, predicting one word at a time. Instead they found that Claude somehow looked ahead, picking the word at the end of the next line several words in advance.

For example, when Claude was given the prompt “A rhyming couplet: He saw a carrot and had to grab it,” the model responded, “His hunger was like a starving rabbit.” But using their microscope, they saw that Claude had already hit upon the word “rabbit” when it was processing “grab it.” It then seemed to write the next line with that ending already in place.

This might sound like a tiny detail. But it goes against the common assumption that large language models always work by picking one word at a time in sequence. “The planning thing in poems blew me away,” says Batson. “Instead of at the very last minute trying to make the rhyme make sense, it knows where it’s going.”

“I thought that was cool,” says Merullo. “One of the joys of working in the field is moments like that. There’s been maybe small bits of evidence pointing toward the ability of models to plan ahead, but it’s been a big open question to what extent they do.”

Anthropic then confirmed its observation by turning off the placeholder component for “rabbitness.” Claude responded with “His hunger was a powerful habit.” And when the team replaced “rabbitness” with “greenness,”Claude responded with “freeing it from the garden’s green.”

Anthropic also explored why Claude sometimes made stuff up, a phenomenon known as hallucination. “Hallucination is the most natural thing in the world for these models, given how they’re just trained to give possible completions,” says Batson. “The real question is, ‘How in God’s name could you ever make it not do that?’”

The latest generation of large language models, like Claude 3.5 and Gemini and GPT-4o, hallucinate far less than previous versions, thanks to extensive post-training (the steps that take an LLM trained on text scraped from most of the internet and turn it into a usable chatbot). But Batson’s team was surprised to find that this post-training seems to have made Claude refuse to speculate as a default behavior. When it did respond with false information, it was because some other component had overridden the “don’t speculate” component.

This seemed to happen most often when the speculation involved a celebrity or other well-known entity. It’s as if the amount of information available on a subject pushed the speculation through, despite the default setting. When Anthropic overrode the “don’t speculate” component to test this, Claude produced lots of false statements about individuals, including claiming that Batson was famous for inventing the Batson principle (he isn’t).

Still unclear

Because we know so little about large language models, any new insight is a big step forward. “A deep understanding of how these models work under the hood would allow us to design and train models that are much better and stronger,” says Biran.

But Batson notes there are still serious limitations. “It’s a misconception that we’ve found all the components of the model or, like, a God’s-eye view,” he says. “Some things are in focus, but other things are still unclear—a distortion of the microscope.”

And it takes several hours for a human researcher to trace the responses to even very short prompts. What’s more, these models can do a remarkable number of different things, and Anthropic has so far looked at only 10 of them.

Batson also says there are big questions that this approach won’t answer. Circuit tracing can be used to peer at the structures inside a large language model, but it won’t tell you how or why those structures formed during training. “That’s a profound question that we don’t address at all in this work,” he says.

But Batson does see this as the start of a new era in which it is possible, at last, to find real evidence for how these models work: “We don’t have to be, like: ‘Are they thinking? Are they reasoning? Are they dreaming? Are they memorizing?’ Those are all analogies. But if we can literally see step by step what a model is doing, maybe now we don’t need analogies.”