EXPERT INSIGHTSPublished Jun 26, 2025

Note: This publication was revised on June 27, 2025, to update the example organizations in Figure 1 following recommendations from subject-matter experts.

China wants to become the global leader in artificial intelligence (AI) by 2030.[1]To achieve this goal, Beijing is deploying industrial policy tools across the full AI technology stack, from chips to applications. This expansion of AI industrial policy leads to two questions: What is Beijing doing to support its AI industry, and will it work?

China’s AI industrial policy will likely accelerate the country’s rapid progress in AI, particularly through support for research, talent, subsidized compute, and applications. Chinese AI models are closing the performance gap with top U.S. models, and AI adoption in China is growing quickly across sectors, from electric vehicles and robotics to health care and biotechnology.[2] Although most of this growth is driven by innovation at China’s private tech firms, state support has helped enhance the competitiveness of China’s AI industry.

However, some aspects of China’s AI industrial policy are wasteful, such as the inefficient allocation of AI chips to companies.[3] Other bottlenecks are hard to overcome, even with massive state support: U.S.-led export controls on AI chips and the semiconductor manufacturing equipment needed to produce such chips are limiting the compute available to Chinese AI developers.[4]Limited access to compute forces Chinese companies to make trade-offs between investing in near-term progress in model development and building longer-term resilience to sanctions.

Ultimately, despite some waste and conflicting priorities, China’s AI industrial policy will help Chinese companies compete with U.S. AI firms by providing talent and capital to an already strong sector. China’s AI development will likely remain at least a close second place behind that of the United States, as such development benefits from both private market competition and the Chinese government’s investments.

Beijing’s AI Policy Goals and Tools

The policy goals and discourse surrounding AI are different in China than in the United States. Chinese leaders want AI to advance the country’s economic development and military capabilities. In Washington, the AI policy discourse is sometimes framed as a “race to AGI [artificial general intelligence].”[5] In contrast, in Beijing, the AI discourse is less abstract and focuses on economic and industrial applications that can support Beijing’s overall economic objectives.

By 2030, Beijing is aiming for AI to become a $100 billion industry and to create more than $1 trillion of additional value in other industries.[6]This goal includes leveraging AI to upgrade traditional sectors, such as health care, manufacturing, and agriculture. It also includes harnessing AI to power emerging industries, particularly hard techsectors with physical applications, such as robotics, autonomous vehicles, and unmanned systems.

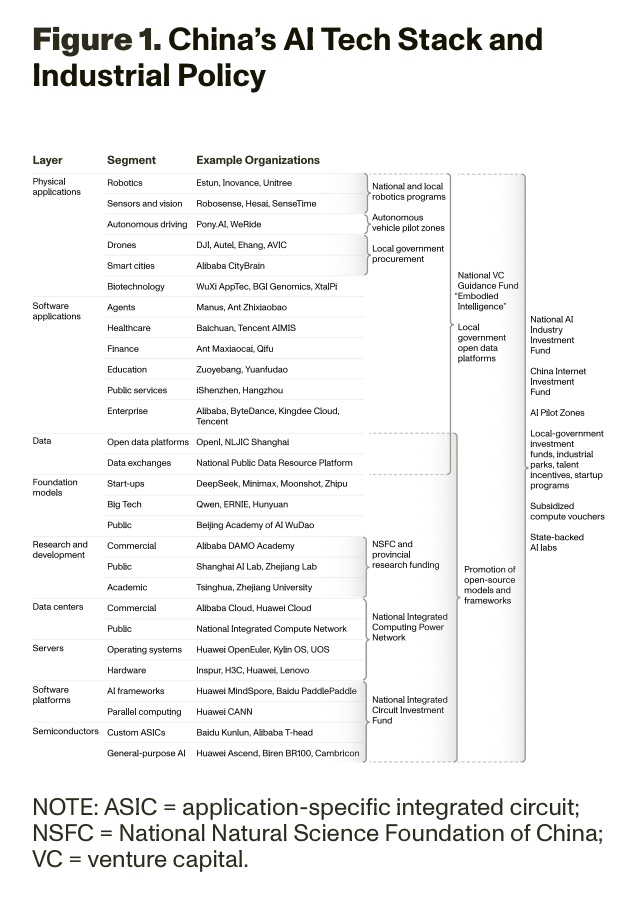

Beijing is using a wide variety of policy tools (see Figure 1). State-led AI investment funds are pouring capital into the development of AI models and applications, including an $8.2 billion AI fund for start-ups.[7] China is building a National Integrated Computing Network to pool computing resources across public and private data centers.[8]Local governments from Shanghai to Shenzhen have set up state-backed AI labs and AI pilot zones to accelerate AI research and talent development.[9] All of this state support comes on top of tens of billions of dollars in private AI investment from Chinese tech companies, such as Alibaba and ByteDance. Still, such investment trails private investments in the United States, such as OpenAI’s Stargate Project investment of $100–500 billion.

U.S. Export Controls to Constrain China’s Compute

Intensifying geopolitical tensions, particularly with the United States, have reshaped China’s AI industrial policy—along with its broader techno-industrial policies—to focus more on self-reliance and strategic competition. Export controls have cut off China’s access to advanced computing chips that are critical to AI development and deployment.[12]Chinese AI firms, such as ByteDance and Baidu, already complain about being compute constrained; as the demand for compute for AI development and deployment grows, the lack of access to advanced chips could significantly limit the growth of China’s AI industry.[13] In addition, export controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment that date back to 2018 have cut off China’s access to advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, delaying Chinese efforts to mass-produce domestic AI chips by years.[14]

The United States enjoys a large lead in total compute capacity, partly because of export controls.[15]Circumventing or mitigating the impact of U.S.-led export restrictions on advanced semiconductors has become a focus of Beijing’s AI policy efforts. At an April 2025 Politburo meeting on AI, Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasized “self-reliance” and the creation of an “autonomously controllable” AI hardware and software ecosystem.[16]

In terms of AI chips, Beijing is supporting the development of domestic alternatives to Nvidia graphics processing units (GPUs), such as Huawei’s Ascend series, which lag behind in performance and production volume.[17] Relying on fewer and less powerful chips forces companies to ration their computing power, reducing the number and size of training and model deployment workloads they can conduct at any one time, and fewer than ten models have been trained on Huawei hardware.[18]

In addition, Chinese AI firms are pursuing other strategies to bypass export controls and access banned Nvidia GPUs, including chip stockpiling, chip smuggling, and building data centers around the world, from Mexico to Malaysia.[19]Therefore, although export controls are important for the U.S. goal of slowing China’s AI development, they are unlikely to halt China’s AI progress altogether and likely will bolster aspects of China’s chip industry.[20]

Another issue that Chinese AI developers are facing is a lack of mature alternatives to U.S. software. To overcome this limitation and promote self-reliance, Beijing is funding Denglin Technology and Moore Threads to develop alternatives to Nvidia’s CUDA software.[21] For AI frameworks, Beijing is supporting the adoption of Huawei’s MindSpore and Baidu’s PaddlePaddle as alternatives to Meta’s PyTorch and Google’s TensorFlow.[22] However, these frameworks still lag behind U.S. ones in terms of adoption, receiving much less attention on GitHub compared with U.S. repositories.[23]

Although China’s domestic platform alternatives lag behind their international counterparts in adoption and capabilities, such software alternatives could reduce the cost of switching from a superior U.S. hardware stack to less mature Chinese AI chips. For now, however, the Chinese alternatives to the Western AI software stack appear to be too immature to fully substitute for Western frameworks. This may change, however, should such alternatives mature and establish themselves as a true alternative ecosystem. This dynamic is reflective of the overall state of Chinese measures to build resilience against U.S. export controls: Such measures are not yet sufficient to overcome the significant limitations that export controls have imposed but have the potential to provide alternatives to the Western semiconductor and software stack.

Will China’s AI Policies Work?

Will China’s state support allow its AI ecosystem to catch up to or even surpass that of the United States and its allies? It is too early in the industry’s development to confidently answer. Overall, however, the state support probably will not hurt, as the policies that China is prioritizing appear, on net, to be targeted to the key needs of the AI industry as a whole.

China’s state support will be essential for its AI progress, particularly in addressing three critical bottlenecks. First, as discussed above, developing domestic AI chips and a sanction-resistant semiconductor supply chain is make-or-break for competing against U.S.-led export controls. Second, despite strong AI research rankings, China’s AI leaders identify talent shortages as a key constraint.[24] Success in these areas will determine whether state support can help enable China’s goal of global AI leadership. Third, China must rapidly scale energy production to meet a projected threefold increase in data center demand by 2030, although China is able to build new power plants much faster than the United States and is therefore likely to be able to meet this challenge.[25]

At the same time, China’s AI industrial policy could be counterproductive in several ways. First, pressure on Chinese AI companies to use less advanced, homegrown alternatives to global platforms will likely slow their progress in developing frontier models, at least over the next several years.[26] iFlytek, which claims to have the only public AI model fully trained with Chinese-made compute hardware aside from Huawei’s models, said that the switch from Nvidia to Huawei chips (including the Ascend 910B) caused a three-month delay in development time.[27]Second, if scarce AI chips are not allocated efficiently, resources could be diverted from more-productive users, such as private tech companies.

Third, Chinese AI firms that receive state support may come under greater scrutiny by the United States and other countries, prompting restrictions that might limit the ability of those firms to access critical resources, such as advanced chips, or to enter international markets. For example, DeepSeek’s sudden rise to prominence has prompted U.S. officials and institutions to restrict its access to U.S. technology, limiting its use.[28]DeepSeek has already been banned on government devices by such states as Texas, New York, and Virginia and by federal bodies, such as the Department of Defense, Department of Commerce, and NASA.[29]

AI is fundamentally different from other sectors in which China has used industrial policy, such as shipbuilding and electric vehicles, partly because of AI development’s reliance on fast-changing, wide-ranging innovation. Frequent paradigm shifts, such as the emergence of reasoning models, and a lack of consensus about AI’s trajectory make it difficult to carry out long-term state planning. Unlike many traditional sectors, the AI industry relies heavily on intangible inputs, such as talent and data, which are less responsive to capital subsidies and harder for the state to control. Although state support can help in some areas, such as capital-intensive computing infrastructure, other areas (such as progress on foundation models and applications) will primarily be driven by the private sector.

The fact that the United States is competitive in AI without any meaningful state support (at least financially) and instead based on private-sector investment and research suggests that industrial policy may not be an essential ingredient for AI competitiveness, unlike other industries. AI has a large and growing private market that can draw in companies and investors and that is already valued at $750 billion and forecast to continue to grow.[30]Furthermore, China’s private-sector companies, such as DeepSeek, have led the development of AI rather than state firms, suggesting that the private sector may have the advantage in driving innovation in this sector.

China’s progress on AI is likely to continue to be driven by its innovative private tech firms and start-ups. Insofar as China’s industrial policy synergizes with or supports that private ecosystem, such policy is likely to help private AI development succeed and therefore “work” from Beijing’s perspective. Where such industrial policy does not clearly link to the private AI ecosystem’s needs and challenges, it is more likely to be wasted. And even with massive state subsidies, Chinese AI developers will have to attract substantially more private investment if they want to close the AI investment gap: Currently, U.S. AI companies receive more than ten times as much private investment as their Chinese counterparts, according to one estimate.[31]

Whether Chinese AI “surpasses” Western providers will also depend on the innovations of the private sector. Even if Chinese AI does not surpass Western offerings, it is likely to remain a close competitor because of the vibrant mixture of private innovation and public support that is already in place.

China’s Layered State Support for AI

China’s AI industrial policy is multilayered, including initiatives across much of the AI stack and efforts that are not explicitly in support of AI but nonetheless are helpful to the Chinese AI industry. Although a major area of Chinese state support is in alternatives to semiconductors and other export-controlled components, state support also stretches into such areas as energy and data center construction, which are necessary for AI success. In this appendix, we take a deeper look at these policies across the AI tech stack.

Energy

China’s AI industry enjoys an energy advantage for data centers, driven by aggressive state-backed power infrastructure expansion and the strategic deployment of renewables at large-scale computing hubs.[32]China’s ability to quickly build and connect new power plants removes a key bottleneck for data center expansion that the United States is grappling with.[33] Moreover, China’s energy abundance allows Chinese AI firms to use less-energy-efficient, homegrown AI hardware, such as Huawei’s CloudMatrix 384 cluster.[34]

In 2021, China’s State Grid Corporation estimated that its data center electricity demand would double from more than 38 gigawatts (GW) in 2020 to more than 76 GW, making up 3.7 percent of its total electricity demand.[35] Beijing has made renewable energy expansion and energy efficiency a central focus of its data center expansion strategy, although coal still made up 58 percent of China’s overall power generation mix in 2024.[36] China’s data center build-out benefits from the country’s broader ability to rapidly add grid capacity at scale. In 2024 alone, China added 429 GW of net new power generation capacity overall, more than 15 times the net capacity added in the United States during the same period.[37]

China’s historic success in developing new energy generation and its continued investments in this space suggest that China will be able to meet the increased power demands of deploying AI and could provide subsidized electricity to AI developers and deployers, which could reduce the operating costs associated with AI.

Chips

As discussed above, China is pursuing a large-scale industrial policy effort aimed at developing a self-reliant semiconductor supply chain. Although this effort was not originally targeted at AI, it has become critical to China’s AI industry as demand for compute skyrockets and U.S.-led export controls limit China’s access to AI chips and the equipment needed to produce them.[38]

Beijing is supporting the development of domestic AI chips, such as Huawei’s Ascend series, as alternatives to AI chips from Nvidia and AMD. Beijing is also pushing Chinese AI companies to switch to domestic AI chips.[39] DeepSeek is experimenting with Huawei Ascend 910C chips for inference, while ByteDance and Ant Group are using Huawei Ascend 910B chips for model training.[40] However, Chinese AI chips have yet to find adoption for AI training workloads. Among Epoch AI’s 321 notable AI models with known hardware types, 319 have been trained on U.S. AI chips, and only two have been trained on Chinese hardware.[41] Even DeepSeek’s recent AI training run still used Nvidia’s GPUs, highlighting that Chinese hardware is not yet mature enough for large-scale AI model training, though it has been used for inference on trained models.[42]

Attempting to close the gap in AI chip manufacturing, Beijing is supporting research and development in chipmaking technology to overcome U.S.-led export controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment, such as extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines from the Dutch firm ASML. This includes research on EUV lithography, multi-patterning, and advanced packaging technology.[43]Beijing has backed these efforts with large-scale public funding programs, such as the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (also known as the “Big Fund”), with the latest round reaching $47 billion.[44] Huawei plays a central role in this effort by recruiting industry talent, partnering with national labs, and sending task forces to support domestic firms.[45] Although China has made progress in pushing the limits of older manufacturing techniques, China’s chipmaking capabilities remain years behind industry leaders, such as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Computing Infrastructure

The rapid expansion of computing infrastructure is also a top priority for Chinese policymakers and could provide Chinese tech companies (particularly start-ups, as well as small and medium-sized firms) with much-needed access to scarce compute resources. Beijing is developing a National Integrated Computing Network that will integrate private and public cloud computing resources into a single nationwide platform that can optimize the allocation of compute resources.[46] Beijing launched the “Eastern Data, Western Computing” initiative in 2022 as part of this effort, aimed at building eight “national computing hubs,” particularly in western provinces with abundant clean energy resources.[47]

By June 2024, China had 246 EFLOP/s of total compute capacity—including both public and commercial data centers—and aims to reach 300 EFLOP/s by 2025, according to the 2023 Action Plan for the High-Quality Development of Computing Power Infrastructure.[48]However, not all of this compute is intended for or well suited to supporting AI workloads. Other research suggests that China controls about 15 percent of total AI compute, while the United States controls about 75 percent of that total.[49] This demonstrates the significant deficit in computing infrastructure that China’s AI industry faces and that state support might attempt to alleviate as China begins to scale the deployment of its models.

Research and Talent

Beijing’s support for basic research and talent development is a key enabler for China’s AI industry. Beijing provides funding for fundamental AI research at universities and state-backed AI labs through several channels, including grants from China’s National Natural Science Foundation and its National Key Research and Development Programs.[50] This public AI research funding has helped turn China’s universities and research labs into world-class AI research centers. Chinese-affiliated authors made up the second-largest share of highly cited AI researchers as of 2024.[51]

Chinese universities and AI firms work closely together, sharing breakthroughs and forming a broader AI research community. One of DeepSeek’s seminal research papers on mixture-of-experts models was co-authored with researchers at Tsinghua University, Peking University, and Nanjing University.[52]More than half of DeepSeek’s AI researchers were trained exclusively at Chinese universities, including founder Liang Wenfeng, who graduated from Zhejiang University.[53] China has been expanding AI education and training across the board, from primary schools to universities.[54] Some of these efforts are more symbolic than substantive, such as AI classes for six-year-olds and the proliferation of university courses on DeepSeek.[55] But Beijing’s efforts to cultivate a deep, highly integrated network of top-tier AI researchers across universities, AI labs, and tech firms directly underpins the ability of China’s AI industry to operate at the global frontier.

State-Backed AI Labs

China’s state-backed AI labs play a critical role in carrying out fundamental research, coordinating common industry standards, developing road maps, and fostering talent.[56] Beijing supports AI research at State Key Laboratories, such as the State Key Laboratory of Intelligent Technology and Systems at Tsinghua University.[57]

As an example, Zhejiang Lab in Hangzhou is one of China’s premier state-backed AI labs and conducts research in a wide variety of fields, from quantum sensing to industrial AI.[58] It was established in 2017 by the Zhejiang Provincial Government in partnership with Zhejiang University and Alibaba. The Shanghai AI Lab is another prominent AI lab that has developed widely used AI benchmarks, such as MVBench, as well as a world-class reasoning model called InternLM3.[59] Peng Cheng Lab, a state-backed AI lab in Shenzhen, has played an important role in supporting the development of frontier AI models by Baidu and Huawei.[60] These labs blur the line between private- and public-sector AI development in China, with state-backed labs supporting both Chinese government programs and private-sector AI development.

Beijing also has two major AI labs created by China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and the Beijing Municipal Government. The Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI), also called the Zhiyuan Institute, is known for its work on AI safety and standards, foundational theory, and the development of open-source frontier models, such as WuDao and Emu3.[61]The Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence is unique in explicitly focusing on AGI through an alternative approach based on human cognition.[62] Both Beijing labs work closely with Peking University and Tsinghua University and offer talent development programs.

The exact impact of China’s state-backed AI labs is difficult to estimate; China’s most advanced and most widely adopted AI models were developed primarily by private companies. However, Chinese AI labs also provide incubators for talent that can later support China’s private-sector AI growth and support government priorities across the tech sector.

AI-Specific Funding

Beijing is also increasing public funding for China’s AI industry through specialized industry funds, bank loan programs, and local government funding. Although there likely will be significant waste in the process, public funding will help support a growing AI start-up ecosystem, particularly for applications. In January 2025, China launched an $8.2 billion National AI Industry Investment Fund.[63] China’s broader $138 billion National Venture Capital Guidance Fund will target several AI-related fields, such as robotics and “embodied intelligence.”[64] Local governments, such as Hangzhou and Beijing, have followed suit with their own state-led AI investment funds.[65]

Major banks have also launched AI industry lending programs, most notably including the Bank of China’s five-year, $138 billion financing program for AI-related industries.[66]Other banks, such as the People’s Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), have launched financing programs for the tech industry, which will likely include funding for AI specifically.[67] Many of these AI and tech funds were launched this year.

Local Government Support

Local governments have also taken a role in promoting AI within China. Although most efforts to transform inland cities into AI hubs are unlikely to succeed, efforts in such cities as Shenzhen and Hangzhou to build on their existing strengths as global tech hubs will significantly enhance China’s national AI capabilities. Shanghai was singled out by Xi during an April 2025 visit, when he called on the city to take the lead on AI development and promoted the Shanghai Foundation Model Innovation Center (an AI start-up incubator) and the city’s ability to attract foreign talent.[68]

China is also developing AI pilot zones across 20 cities, where AI companies can receive special financing and operate in a favorable regulatory environment.[69] Local governments often provide funding for start-ups through public investment funds and “computing vouchers” that offer subsidized access to computing resources.[70]Cities such as Beijing and Ningxia have set up computing exchange platforms to more effectively allocate compute resources across regions and data centers.[71]

Following Beijing’s lead, many Chinese cities have launched AI and “AI+” action plans aimed at supporting local start-ups and promoting AI adoption in other sectors. The Beijing city government’s AI+ action plan aims to integrate AI into government services and build a shared computing platform for training large language models (LLMs).[72] Shenzhen has launched an AI action plan aimed at building a 4,000 PFLOP/s intelligent computing center (the equivalent of about 4,000 Nvidia H100s).[73]

Promoting Open Source

Beijing promotes open-source AI platforms, datasets, and models, which it views as a way to accelerate industry progress and circumvent potential export controls on proprietary technology. This open-source approach also allows China to potentially shape AI industry standards abroad through the adoption of its low-cost, open-source offerings.[74] China has been promoting its open-source AI collaboration platform called OpenI, in which participants can share AI models and datasets and access computing resources, though it is in its infancy in comparison with Western platforms, such as Hugging Face.[75]

Beijing has also been encouraging greater use of a Chinese alternative to Microsoft-owned GitHub called Gitee, which claims to have more than 13.5 million registered users, compared with GitHub’s more than 100 million users.[76] In addition to providing a domestic platform that is safe from U.S. policy action, Gitee allows Beijing to enforce greater censorship control.[77] However, subjecting code to a political review process on Gitee slows software development and makes the platform much less attractive to non-Chinese users.[78] Lastly, commercial players are also embracing open-source AI models after the success of DeepSeek’s R1 model.[79] Although an open-source approach spurs greater adoption and increases opportunities for commercialization, there are questions as to whether Beijing will continue to tolerate the corresponding more-limited censorship and state control that come with open-source models.[80]

Data

Beijing is also aiming to turn data into a strategic resource to give China an edge in AI, although efforts to date have been mixed.[81] Beijing wants to turn data into a new “factor of production” and has modified accounting rules to allow firms to classify data as intangible assets.[82]Local governments have established data marketplaces, such as the Shenzhen Data Exchange, to allow data to be traded by private firms, state-owned enterprises, and state agencies. China’s National Data Administration is preparing to launch a National Public Data Resource Platform to facilitate data trading on a national scale.[83] However, although Beijing has been pushing organizations to share data on these public exchanges, private firms are often reluctant to share their data because of concerns related to control risks and compliance with data protection laws.[84]

Instead, Beijing’s support for open data-sharing platforms is likely to play a greater role in advancing China’s AI industry by increasing general access to large training sets without the ownership complexities of a data trading exchange. State support for open data-sharing include open data platforms, such as OpenI, as well as the creation of open datasets, such as FlagData, BAAI’s Chinese multimodal dataset.[85]Beijing is particularly focused on promoting data-sharing for robotics through such institutions as the Beijing Embodied Artificial Intelligence Robotics Innovation Center and the National Local Joint Humanoid Robot Innovation Center in Shanghai.[86] Several leading Chinese robotics companies, such as AgiBot and Fourier, also have released open training datasets, augmenting the country’s broader pool of robotics training data.[87]

Applications

Finally, Beijing has begun directly promoting the adoption of AI applications across all sectors of society as part of its AI industrial policy. In an April 2025 Politburo meeting on AI, Xi argued that China’s AI industry should be “strongly oriented toward applications.”[88]National AI plans, such as the 2017 AI development plan, as well as local government AI+ action plans, focus heavily on AI integration into public services and government operations.[89] China’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, the parent organization that controls China’s most powerful central state firms, is also pushing AI integration across its member state-owned enterprises.[90]

Beijing is seeking to integrate AI into a wide variety of sectors in addition to government services. These include traditional sectors, from manufacturing and agriculture to education and health care, as well as emerging fields. In particular, Beijing is prioritizing AI development in robotics and “embodied intelligence.”[91] China released the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Robot Industry in 2021, followed by the Robot+ Application Action Plan in 2023 aimed at spurring the development and adoption of robots.[92]

Article link: https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA4012-1.html?