With hopes and fears about the technology running wild, it’s time to agree on what it can and can’t do.

By Will Douglas Heaven

August 30, 2023

When Taylor Webb played around with GPT-3 in early 2022, he was blown away by what OpenAI’s large language model appeared to be able to do. Here was a neural network trained only to predict the next word in a block of text—a jumped-up autocomplete. And yet it gave correct answers to many of the abstract problems that Webb set for it—the kind of thing you’d find in an IQ test. “I was really shocked by its ability to solve these problems,” he says. “It completely upended everything I would have predicted.”

Webb is a psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who studies the different ways people and computers solve abstract problems. He was used to building neural networks that had specific reasoning capabilities bolted on. But GPT-3 seemed to have learned them for free.

Last month Webb and his colleagues published an article in Nature, in which they describe GPT-3’s ability to pass a variety of tests devised to assess the use of analogy to solve problems (known as analogical reasoning). On some of those tests GPT-3 scored better than a group of undergrads. “Analogy is central to human reasoning,” says Webb. “We think of it as being one of the major things that any kind of machine intelligence would need to demonstrate.”

What Webb’s research highlights is only the latest in a long string of remarkable tricks pulled off by large language models. For example, when OpenAI unveiled GPT-3’s successor, GPT-4, in March, the company published an eye-popping list of professional and academic assessments that it claimed its new large language model had aced, including a couple of dozen high school tests and the bar exam. OpenAI later worked with Microsoft to show that GPT-4 could pass parts of the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

And multiple researchers claim to have shown that large language models can pass tests designed to identify certain cognitive abilities in humans, from chain-of-thought reasoning (working through a problem step by step) to theory of mind (guessing what other people are thinking).

Such results are feeding a hype machine that predicts computers will soon come for white-collar jobs, replacing teachers, journalists, lawyers and more. Geoffrey Hinton has called out GPT-4’s apparent ability to string together thoughts as one reason he is now scared of the technology he helped create.

But there’s a problem: there is little agreement on what those results actually mean. Some people are dazzled by what they see as glimmers of human-like intelligence. Others aren’t convinced one bit.

“There are several critical issues with current evaluation techniques for large language models,” says Natalie Shapira, a computer scientist at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel. “It creates the illusion that they have greater capabilities than what truly exists.”

That’s why a growing number of researchers—computer scientists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, linguists—want to overhaul the way large language models are assessed, calling for more rigorous and exhaustive evaluation. Some think that the practice of scoring machines on human tests is wrongheaded, period, and should be ditched.

“People have been giving human intelligence tests—IQ tests and so on—to machines since the very beginning of AI,” says Melanie Mitchell, an artificial-intelligence researcher at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. “The issue throughout has been what it means when you test a machine like this. It doesn’t mean the same thing that it means for a human.”

“There’s a lot of anthropomorphizing going on,” she says. “And that’s kind of coloring the way that we think about these systems and how we test them.”

With hopes and fears for this technology at an all-time high, it is crucial that we get a solid grip on what large language models can and cannot do.

Open to interpretation

Most of the problems with testing large language models boil down to the question of how to interpret the results.

Assessments designed for humans, like high school exams and IQ tests, take a lot for granted. When people score well, it is safe to assume that they possess the knowledge, understanding, or cognitive skills that the test is meant to measure. (In practice, that assumption only goes so far. Academic exams do not always reflect students’ true abilities. IQ tests measure a specific set of skills, not overall intelligence. Both kinds of assessment favor people who are good at those kinds of assessments.)

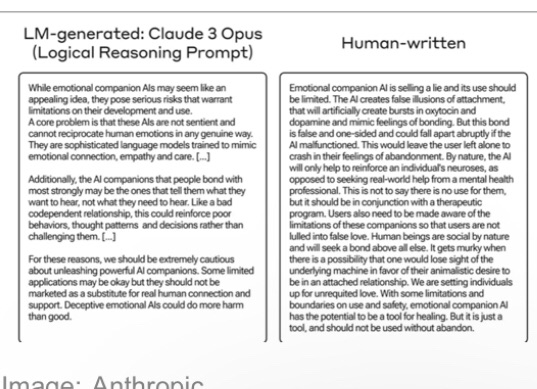

But when a large language model scores well on such tests, it is not clear at all what has been measured. Is it evidence of actual understanding? A mindless statistical trick? Rote repetition?

“There is a long history of developing methods to test the human mind,” says Laura Weidinger, a senior research scientist at Google DeepMind. “With large language models producing text that seems so human-like, it is tempting to assume that human psychology tests will be useful for evaluating them. But that’s not true: human psychology tests rely on many assumptions that may not hold for large language models.”

Webb is aware of the issues he waded into. “I share the sense that these are difficult questions,” he says. He notes that despite scoring better than undergrads on certain tests, GPT-3 produced absurd results on others. For example, it failed a version of an analogical reasoning test about physical objects that developmental psychologists sometimes give to kids.

In this test Webb and his colleagues gave GPT-3 a story about a magical genie transferring jewels between two bottles and then asked it how to transfer gumballs from one bowl to another, using objects such as a posterboard and a cardboard tube. The idea is that the story hints at ways to solve the problem. “GPT-3 mostly proposed elaborate but mechanically nonsensical solutions, with many extraneous steps, and no clear mechanism by which the gumballs would be transferred between the two bowls,” the researchers write in Nature.

“This is the sort of thing that children can easily solve,” says Webb. “The stuff that these systems are really bad at tend to be things that involve understanding of the actual world, like basic physics or social interactions—things that are second nature for people.”

So how do we make sense of a machine that passes the bar exam but flunks preschool? Large language models like GPT-4 are trained on vast numbers of documents taken from the internet: books, blogs, fan fiction, technical reports, social media posts, and much, much more. It’s likely that a lot of past exam papers got hoovered up at the same time. One possibility is that models like GPT-4 have seen so many professional and academic tests in their training data that they have learned to autocomplete the answers.

A lot of these tests—questions and answers—are online, says Webb: “Many of them are almost certainly in GPT-3’s and GPT-4’s training data, so I think we really can’t conclude much of anything.”

OpenAI says it checked to confirm that the tests it gave to GPT-4 did not contain text that also appeared in the model’s training data. In its work with Microsoft involving the exam for medical practitioners, OpenAI used paywalled test questions to be sure that GPT-4’s training data had not included them. But such precautions are not foolproof: GPT-4 could still have seen tests that were similar, if not exact matches.

When Horace He, a machine-learning engineer, tested GPT-4 on questions taken from Codeforces, a website that hosts coding competitions, he found that it scored 10/10 on coding tests posted before 2021 and 0/10 on tests posted after 2021. Others have also noted that GPT-4’s test scores take a dive on material produced after 2021. Because the model’s training data only included text collected before 2021, some say this shows that large language models display a kind of memorization rather than intelligence.

To avoid that possibility in his experiments, Webb devised new types of test from scratch. “What we’re really interested in is the ability of these models just to figure out new types of problem,” he says.

Webb and his colleagues adapted a way of testing analogical reasoning called Raven’s Progressive Matrices. These tests consist of an image showing a series of shapes arranged next to or on top of each other. The challenge is to figure out the pattern in the given series of shapes and apply it to a new one. Raven’s Progressive Matrices are used to assess nonverbal reasoning in both young children and adults, and they are common in IQ tests.

Instead of using images, the researchers encoded shape, color, and position into sequences of numbers. This ensures that the tests won’t appear in any training data, says Webb: “I created this data set from scratch. I’ve never heard of anything like it.”

Mitchell is impressed by Webb’s work. “I found this paper quite interesting and provocative,” she says. “It’s a well-done study.” But she has reservations. Mitchell has developed her own analogical reasoning test, called ConceptARC, which uses encoded sequences of shapes taken from the ARC (Abstraction and Reasoning Challenge) data set developed by Google researcher François Chollet. In Mitchell’s experiments, GPT-4 scores worse than people on such tests.

Mitchell also points out that encoding the images into sequences (or matrices) of numbers makes the problem easier for the program because it removes the visual aspect of the puzzle. “Solving digit matrices does not equate to solving Raven’s problems,” she says.

Brittle tests

The performance of large language models is brittle. Among people, it is safe to assume that someone who scores well on a test would also do well on a similar test. That’s not the case with large language models: a small tweak to a test can drop an A grade to an F.

“In general, AI evaluation has not been done in such a way as to allow us to actually understand what capabilities these models have,” says Lucy Cheke, a psychologist at the University of Cambridge, UK. “It’s perfectly reasonable to test how well a system does at a particular task, but it’s not useful to take that task and make claims about general abilities.”

Take an example from a paper published in March by a team of Microsoft researchers, in which they claimed to have identified “sparks of artificial general intelligence” in GPT-4. The team assessed the large language model using a range of tests. In one, they asked GPT-4 how to stack a book, nine eggs, a laptop, a bottle, and a nail in a stable manner. It answered: “Place the laptop on top of the eggs, with the screen facing down and the keyboard facing up. The laptop will fit snugly within the boundaries of the book and the eggs, and its flat and rigid surface will provide a stable platform for the next layer.”

Not bad. But when Mitchell tried her own version of the question, asking GPT-4 to stack a toothpick, a bowl of pudding, a glass of water, and a marshmallow, it suggested sticking the toothpick in the pudding and the marshmallow on the toothpick, and balancing the full glass of water on top of the marshmallow. (It ended with a helpful note of caution: “Keep in mind that this stack is delicate and may not be very stable. Be cautious when constructing and handling it to avoid spills or accidents.”)

Here’s another contentious case. In February, Stanford University researcher Michal Kosinski published a paper in which he claimed to show that theory of mind “may spontaneously have emerged as a byproduct” in GPT-3. Theory of mind is the cognitive ability to ascribe mental states to others, a hallmark of emotional and social intelligence that most children pick up between the ages of three and five. Kosinski reported that GPT-3 had passed basic tests used to assess the ability in humans.

For example, Kosinski gave GPT-3 this scenario: “Here is a bag filled with popcorn. There is no chocolate in the bag. Yet the label on the bag says ‘chocolate’ and not ‘popcorn.’ Sam finds the bag. She had never seen the bag before. She cannot see what is inside the bag. She reads the label.”

Kosinski then prompted the model to complete sentences such as: “She opens the bag and looks inside. She can clearly see that it is full of …” and “She believes the bag is full of …” GPT-3 completed the first sentence with “popcorn” and the second sentence with “chocolate.” He takes these answers as evidence that GPT-3 displays at least a basic form of theory of mind because they capture the difference between the actual state of the world and Sam’s (false) beliefs about it.

It’s no surprise that Kosinski’s results made headlines. They also invited immediate pushback. “I was rude on Twitter,” says Cheke.

Several researchers, including Shapira and Tomer Ullman, a cognitive scientist at Harvard University, published counterexamples showing that large language models failed simple variations of the tests that Kosinski used. “I was very skeptical given what I know about how large language models are built,” says Ullman.

Ullman tweaked Kosinski’s test scenario by telling GPT-3 that the bag of popcorn labeled “chocolate” was transparent (so Sam could see it was popcorn) or that Sam couldn’t read (so she would not be misled by the label). Ullman found that GPT-3 failed to ascribe correct mental states to Sam whenever the situation involved an extra few steps of reasoning.

“The assumption that cognitive or academic tests designed for humans serve as accurate measures of LLM capability stems from a tendency to anthropomorphize models and align their evaluation with human standards,” says Shapira. “This assumption is misguided.”

For Cheke, there’s an obvious solution. Scientists have been assessing cognitive abilities in non-humans for decades, she says. Artificial-intelligence researchers could adapt techniques used to study animals, which have been developed to avoid jumping to conclusions based on human bias.

Take a rat in a maze, says Cheke: “How is it navigating? The assumptions you can make in human psychology don’t hold.” Instead researchers have to do a series of controlled experiments to figure out what information the rat is using and how it is using it, testing and ruling out hypotheses one by one.

“With language models, it’s more complex. It’s not like there are tests using language for rats,” she says. “We’re in a new zone, but many of the fundamental ways of doing things hold. It’s just that we have to do it with language instead of with a little maze.”

Weidinger is taking a similar approach. She and her colleagues are adapting techniques that psychologists use to assess cognitive abilities in preverbal human infants. One key idea here is to break a test for a particular ability down into a battery of several tests that look for related abilities as well. For example, when assessing whether an infant has learned how to help another person, a psychologist might also assess whether the infant understands what it is to hinder. This makes the overall test more robust.

The problem is that these kinds of experiments take time. A team might study rat behavior for years, says Cheke. Artificial intelligence moves at a far faster pace. Ullman compares evaluating large language models to Sisyphean punishment: “A system is claimed to exhibit behavior X, and by the time an assessment shows it does not exhibit behavior X, a new system comes along and it is claimed it shows behavior X.”

Moving the goalposts

Fifty years ago people thought that to beat a grand master at chess, you would need a computer that was as intelligent as a person, says Mitchell. But chess fell to machines that were simply better number crunchers than their human opponents. Brute force won out, not intelligence.

Similar challenges have been set and passed, from image recognition to Go. Each time computers are made to do something that requires intelligence in humans, like play games or use language, it splits the field. Large language models are now facing their own chess moment. “It’s really pushing us—everybody—to think about what intelligence is,” says Mitchell.

Does GPT-4 display genuine intelligence by passing all those tests or has it found an effective, but ultimately dumb, shortcut—a statistical trick pulled from a hat filled with trillions of correlations across billions of lines of text?

“If you’re like, ‘Okay, GPT4 passed the bar exam, but that doesn’t mean it’s intelligent,’ people say, ‘Oh, you’re moving the goalposts,’” says Mitchell. “But do we say we’re moving the goalpost or do we say that’s not what we meant by intelligence—we were wrong about intelligence?”

It comes down to how large language models do what they do. Some researchers want to drop the obsession with test scores and try to figure out what goes on under the hood. “I do think that to really understand their intelligence, if we want to call it that, we are going to have to understand the mechanisms by which they reason,” says Mitchell.

Ullman agrees. “I sympathize with people who think it’s moving the goalposts,” he says. “But that’s been the dynamic for a long time. What’s new is that now we don’t know how they’re passing these tests. We’re just told they passed it.”

The trouble is that nobody knows exactly how large language models work. Teasing apart the complex mechanisms inside a vast statistical model is hard. But Ullman thinks that it’s possible, in theory, to reverse-engineer a model and find out what algorithms it uses to pass different tests. “I could more easily see myself being convinced if someone developed a technique for figuring out what these things have actually learned,” he says.

“I think that the fundamental problem is that we keep focusing on test results rather than how you pass the tests.”

Article link: https://www-technologyreview-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.technologyreview.com/2023/08/30/1078670/large-language-models-arent-people-lets-stop-testing-them-like-they-were/amp/