Despite billion-dollar investments, the technology faces hurdles that keeps its future uncertain

November 13, 2025

KEY INSIGHTS

- Chemistry problems could be among the first to be solved via quantum computers.

- Companies are already demonstrating how the technology can solve chemistry problems.

- Applications important to industry will require millions of qubits, but other challenges must first be overcome.

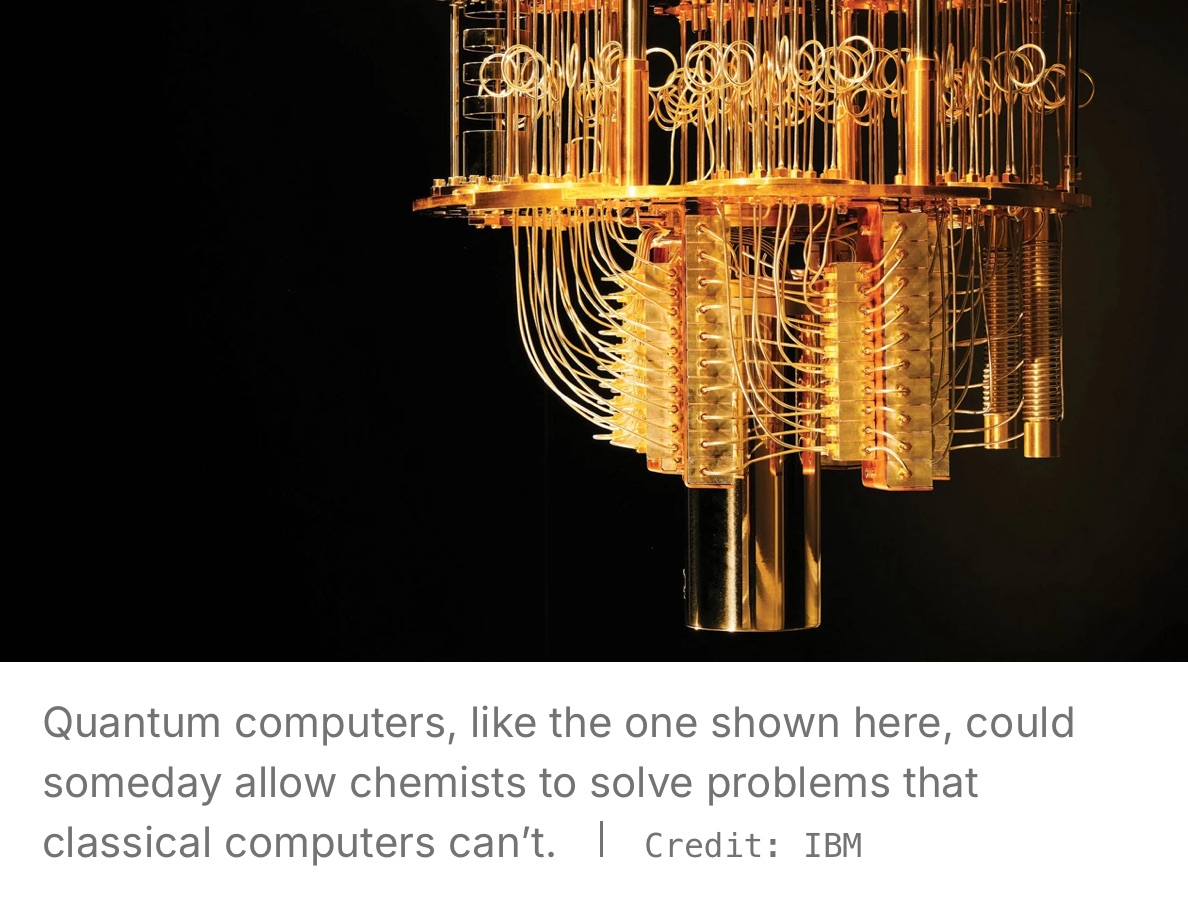

At the 2025 Quantum World Congress, a glittering bronze chandelier with protruding wires hung suspended in a glass case. Around it, a crowd queued to snap photos. For many people there, it was the closest they’ve ever come to a quantum computer.

The meeting, held in September just outside Washington, DC, attracted hundreds of researchers, investors, and executives to talk about technology that could revolutionize computing. But throughout the presentations of breakthroughs that are bringing the potential of quantum computing closer to reality, an uncomfortable truth often went unspoken: the exotic-looking quantum machines have yet to outperform their classical counterparts.

For decades, quantum computing has promised advances in fields as varied as cryptography, navigation, and optimization. And the field where it could bring advantages over classical computing soonest is chemistry. Chemical problems are suited to the technology because molecules are themselves quantum systems. And, in theory, the computers could simulate any part of a quantum system’s behavior.

Artificial intelligence is a once speculative technology that has become crucial in chemistry, and quantum computing is following a similar trajectory, says Alán Aspuru-Guzik, a professor of chemistry at the University of Toronto and senior director of quantum chemistry at the computer chip giant Nvidia. It took decades for AI to go from an uncertain future to a multibillion-dollar industry. Quantum computing may require a similarly long runway between early funding and commercial adoption, he says.

But while the billions of dollars in investment pouring into the quantum computing market this year underline quantum’s potential, experts say the technology has yet to bring practical benefits. The runway is strewn with both hardware and software problems that need to be remedied before the promise can ever be realized. Profits for builders of the computers and the companies that might use them could still be decades away.

What is a quantum computer?

First proposed in the early 1980s by physicist Richard Feynman, quantum computers harness the principles of quantum mechanics—wave-particle duality, superposition, entanglement, and the uncertainty principle—to solve problems. Using qubits—units of information that can be built from different materials and exist in multiple states at once—a quantum computer can process a lot of data in parallel.

Classical computers can model small numbers of qubits by brute-force calculation, but the resources required to crunch those numbers grow exponentially with every added qubit. Classical computers quickly fall behind.

In 1998, a team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley; Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Los Alamos National Laboratory built the first quantum computer using only 2 qubits. Today’s devices, made by a handful of companies, now reach 100 or more qubits, which are contained on chips that resemble those of classical computers.

A team at the Cleveland Clinic has modeled the solvent effects of methanol, ethanol, and methylamine using quantum hardware with an algorithm that samples electron energy. But the model still struggles to capture weak forces like hydrogen bonding and dispersion, says Kenneth Merz, a quantum molecular scientist at the institution who was involved in the study.

Researchers are also developing algorithms that address specific chemical problems. Using a new quantum algorithm, scientists at the University of Sydney achieved the first quantum simulation of chemical dynamics, modeling how a molecule’s structure evolves over time rather than just its static state The quantum computer company IonQ developed a mixed quantum-classical algorithm capable of accurately computing the forces between atoms, and Google recently announced an algorithm that could someday be used for analyzing nuclear magnetic resonance data.

The South Korean quantum algorithm start-up Qunova Computing has built a faster, more accurate version of VQE, says CEO Kevin Rhee. With it, Qunova modeled nitrogen reactions in molecules important for nitrogen fixation. In tests, the method was almost nine times as fast as one done on a classical computer, he says.

Quantum computers are also beginning to be used to model proteins. With the aid of classical processors, a 16-qubit computer found potential drugs that inhibit KRAS, a protein linked to many cancers. And IonQ and the software company Kipu Quantum simulated the folding of a 12-amino-acid chain—the largest protein-folding demonstration on quantum hardware to date.

Quantum’s advantage is still elusive

But many of these use cases don’t claim quantum advantage—the idea that a task can be done better, faster, or cheaper than with classical methods. And the problems being worked on now are too narrow to benefit industry, Merck’s Harbach says. “For academia, it’s about proving the technology. For us, it’s proving the value,” he says.

Many algorithms are restricted in what they can do because getting many qubits to work together is still difficult, Kais says. While companies like Qunova claim their algorithms can successfully handle up to 200 qubits, many chemistry problems will require substantially more.

“For academia, it’s about proving the technology. For us, it’s proving the value.”Philipp Harbach, head of digital innovation at the group science and technology office, Merck KGaA

Modeling cytochrome P450 enzymes or iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) are the kinds of tasks industrial researchers would like to see quantum computing take on. These are complex metalloenzymes that are important to metabolism and nitrogen fixation, respectively, and are difficult for classical computers to simulate.

In 2021, Google estimated that about 2.7 million physical qubits would be needed to model FeMoco; other studies around that time made similar estimates for P450. The French start-up Alice & Bob announced in October that its qubits could reduce the total requirement to a little under 100,000, still far more than what today’s hardware and algorithms can offer.

Tasks such as simulating large biomolecules and designing novel polymers, battery materials, superconductors, and catalysts each would require a similar number of qubits. But scaling quantum systems isn’t easy, because qubits are extremely fragile and easily lose their quantum states.

In the meantime, some companies are developing “quantum-inspired” algorithms, which take techniques that work on a quantum computer and run them on a classical one to solve similar problems, IBM’s Garcia says. Fujitsu, for example, is creating quantum-inspired software to discover a new catalyst for clean hydrogen production, and Toshiba is making optimization algorithms for choosing the best answer in a large dataset. But the inspired algorithms can’t fully replicate a quantum computer, she says.

The fault in our quantum computers

The reason quantum computers have largely failed to do anything better than a classical computer comes down to how qubits work, says Philipp Ernst, head of solutions at PsiQuantum, a quantum computer developer.

The number of qubits in a quantum computer matters. The more qubits it has, the greater its processing power and potential to run complex algorithms that solve larger problems. But qubit quality is just as important: a quantum computer may contain many qubits, but if they’re unstable or can’t interact with one another, the computer doesn’t have much practical use, Ernst says.

Scientists say we are in the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era, which is characterized by low qubit counts and a sensitivity to the environment that causes high error rates and makes computers unreliable.

Quantum noise comes from a lot of places, including thermal fluctuations, electromagnetic interference, material disturbances, and other interactions with the environment. Any amount of noise can mess with qubits by causing them to lose either their superposition or their entanglement.

“Quantum computing is essentially where conventional computing was in the ’60s or ’70s . . . nobody at that point in time came up with or could imagine how AI would be run and used today.”Philipp Ernst, head of quantum solutions, PsiQuantum

For problems like modeling protein folding, noisy qubits are a big issue. “If you try to model 10–15 amino acids, all hell breaks loose. The errors kill you,” Cleveland Clinic researcher Merz says.

Rather than trying to make machines that compensate for errors by piling on the qubits, researchers are pivoting to fault-tolerant computers that can detect and correct errors. These machines use many physical qubits to form a single logical qubit, which stores information redundantly so that if one qubit fails, the system can correct it before data are lost and errors build up.

“You basically need error correction, and you need several hundred logical qubits in order to do something useful,” Ernst says.

Quantum computer companies have made steps toward fault tolerance. Quantinuum recently reported simulating the ground-state energy of hydrogen using error-corrected logical qubits. Microsoft, working in partnership with Quantinuum, demonstrated a record 12 logical qubits operating with high reliability. IBM is developing quantum error-correction codes to reduce the number of physical qubits needed, and Alice & Bob is innovating “cat qubits” that naturally resist certain types of errors.

Most of these companies say they will launch fault-tolerant quantum computers with enough qubits for complex calculations by 2030.

Companies are taking different approaches to make qubits, a unit of information that can be in multiple states at once.

Superconducting

Credit: SpinQ

Technology: Tiny circuits made from materials such as aluminum and niobium that carry current without resistance

Advantage: Run operations quickly

Drawback: Can lose their quantum state quickly

Companies: IBM, Microsoft, Google

Photonic

Credit: Xanadu Quantum Technologies

Technology: Single photons encoding information

Advantage: Stable and can work at room temperature

Drawback: Hard to control photons

Companies: PsiQuantum, Xanadu Quantum Technologies

Trapped ion

Credit: Quantinuum

Technology: Charged atoms suspended in a vacuum and controlled by electromagnetic fields

Advantage: Stable

Drawback: Slow operation speed and hard to scale

Companies: IonQ, Quantinuum

Spin or neutral atom

Credit: Intel

Technology: Atoms held by optical tweezers or single-electron spins confined in solid-state materials

Advantage: Scalable and can operate at temperatures slightly above absolute zero

Drawback: Still in early research phase

Companies: Academic laboratories only

Topological

Credit: Microsoft

Technology: Exotic quasiparticles in 2D materials to encode data

Advantage: Good at maintaining a quantum state

Drawback: Hard to build and still experimental

Companies: Microsoft

Fault tolerance isn’t enough

As the number of qubits grows, getting them to work together becomes harder. In many systems, qubits can easily interact only with their nearest neighbors, and linking distant ones on different chips takes extra steps that slow things down. Making accurate multiqubit gates and managing thousands of control signals to influence the qubits adds to the difficulty.

Quantum computers may one day solve problems faster than classical computers because they can process many possibilities at once, but currently, most quantum processors are actually slower than classical chips. Each step can take thousands of times longer than in modern classical computers.

And because qubits are extremely fragile, their environment must remain stable. Some types of qubits need to operate near absolute zero, and heat is generated as qubits are added. The large installations that are required to do complex calculations need a lot of space and energy to keep everything cold.

Not surprisingly, building a quantum computer isn’t cheap. A single qubit costs around $10,000. Some estimates place a large-scale quantum computer at tens of billions of dollars, while smaller ones that are not fault tolerant are in the mid-to-high tens of millions.

If you have a 100-qubit quantum computer and a classical computer that can solve the same problem, then you have to consider the cost, Qunova’s Rhee says. “The quantum computers will be 10 times or 100 times more expensive.”

Because of costs and space requirements, quantum computing is unfolding as a cloud service. IBM, Google, and Amazon already rent out early-stage quantum processors by the minute. To access IBM’s fleet of quantum computers, prices range from $48 to $96 per minute.

IBM quantum scientist Maika Takita works on a superconducting quantum computer. Credit: IBM

And yet quantum is bringing in billions

Despite the lack of real-world industry applications, and cost and engineering challenges yet to be overcome, investment in quantum computing is robust. Kais says the fear of missing out on the next big thing, as many did in the early days of AI, might be driving investors.

The consulting firm McKinsey & Co. projects the industry could be worth anywhere from $28 billion to $72 billionby 2035, up from $750 million in 2024. In the first quarter of 2025 alone, investors poured $1.25 billion into quantum hardware and over $250 million into software, according to Quantum Insider, a market intelligence firm.

Industry leaders like Quantinuum (valued at $10 billion) and IonQ (valued at nearly $19 billion) continue to draw major backing, while newer companies such as PsiQuantum are raising hundreds of millions of dollars. Governments in the US, China, the European Union, and Japan are also ramping up multimillion-dollar programs to support the technology.

Chemical and pharmaceutical industry players are starting to invest too. In the chemical sector, BASF, Covestro, Johnson Matthey, and Mitsubishi Chemical are partnering with quantum computing vendors to explore materials simulation and catalysis. Major drug companies—including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi—have disclosed quantum initiatives ranging from drug discovery partnerships to internal quantum-algorithm work.

“If [a pharmaceutical company] hasn’t invested yet, they will,” Nvidia’s Aspuru-Guzik says.

But even with rapid progress in quantum computing hardware and software, it’s not yet clear when quantum advantage will arrive and how much it will achieve.

“Quantum computing is essentially where conventional computing was in the ’60s or ’70s . . . nobody at that point in time could imagine how AI would be run and used today,” Ernst says.

While most experts agree that “useful” quantum chemistry is still years away—likely beyond 2030, and possibly not until 2040—they are adamant it will happen.

“There aren’t any fundamental things which prevent us from building these machines . . . it’s more of an engineering type of problem,” North Carolina State’s Kais says. “‘I’m really optimistic that within maybe the next 5 years we’ll start seeing computers solve very, very complex problems.”

Linde Wester Hansen, the head of quantum applications at Alice & Bob, says chemical companies should begin preparing now. Even today, they could benefit from modeling smaller molecules with quantum tools, she says.

Yet quantum computers’ success in chemistry or any other field is not preordained. “It’s not clear that they will have any impact,” SandboxAQ’s Lewis says. “It could be that quantum computers are very expensive prime number factoring machines, or it could be this massive disruptive thing.”

Article link: https://cen.acs.org/business/quantum-computing-chemistrys-next-AI/103/web/2025/11